The Woman of Dreams: The Secret of Ancient Venus Unraveled

Scientists find out why «Paleolithic Venus» was depicted as overweight

«Paleolithic Venuses» created in cold climates were more obese than figures from warmer regions. When cold, the extra weight protected the woman, allowing her to be more likely to bear and nurture a child, so probably the harsher the conditions, the more extra weight was welcomed.

In cold climates, prehistoric sculptors created statuettes of women with more pronounced obesity than in warm climates, experts from the University of Colorado have found. The extra weight provided insulation and served as an additional source of energy during pregnancy and lactation, and therefore was desirable for women. And, the colder the climate, the more fat she had to be. The study was published in the journal Obesity.

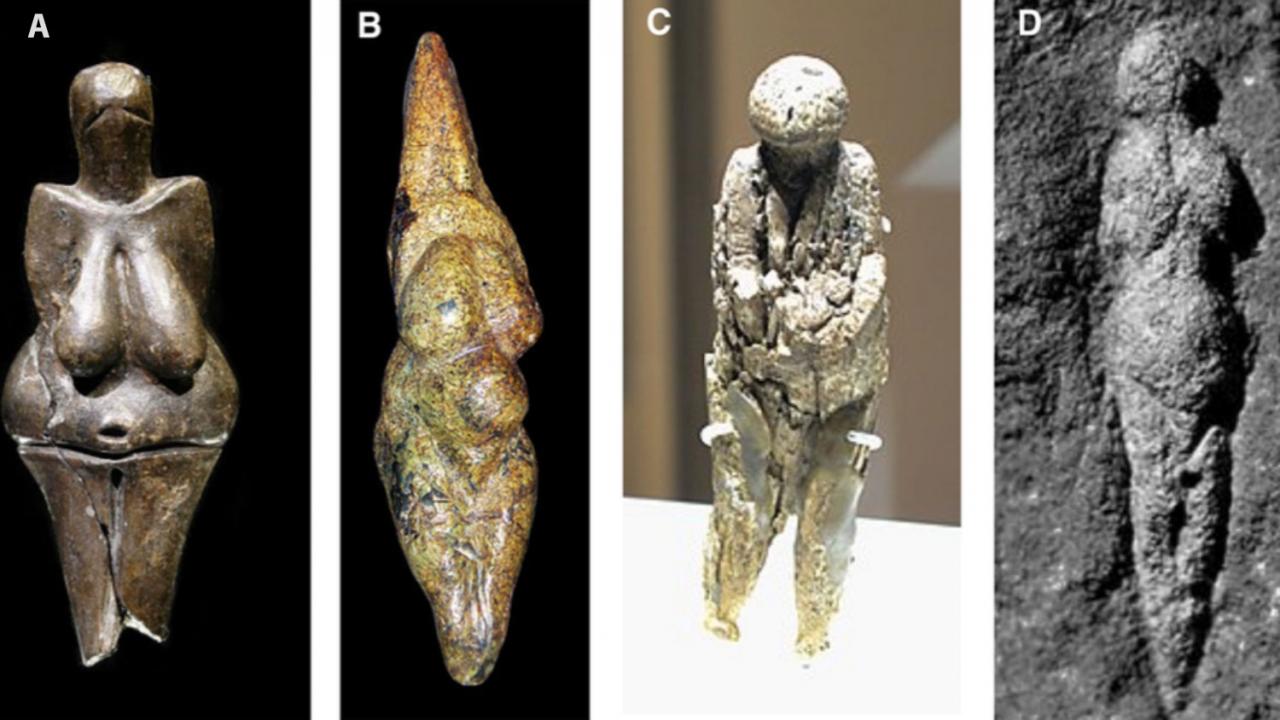

«Paleolithic Venuses» are prehistoric statuettes of women with voluminous breasts, abdomen and buttocks. Their exact purpose is unknown, but it is speculated that the figurines may have been fertility symbols, talismans, or even pornographic images.

- The pronounced obesity of the figures is probably related to the cult of fertility or symbolizes the desire for abundance, fertility and security.

Modern humans appeared in Europe about 48,000 years ago. They hunted deer, horses and mammoths, and in summer berries, nuts and fish formed an important part of their diet.

In those days, as today, the climate was quite variable. Winters became colder and colder; during the coldest months the temperature dropped down to — 50-59 °С. Some tribes died out, others moved south, some were able to adapt to life in the forests. Food was desperately scarce.

Figures of fat women appeared at this time. They were 6-16 cm in height and were made of stone, ivory, horn, and sometimes clay. Most of the figurines depicted women naked, and their creators focused on the torso and sex features, with little attention to the head and limbs.

Many figurines depict women in their childbearing years, some can even be mistaken for images of pregnant women. The figures are characterized by voluminous bellies and buttocks, with clear signs of obesity, although it is doubtful that it was common at the time.

The male figures, however, are not obese — they are elongated and slender. This difference has previously led scientists to the idea that extra weight here acts as a symbol of fertility or beauty.

Now the researchers have noticed that the closer to the glaciers were the settlements where the statuettes were found, the more obese women they depicted. They measured the ratios between the statuettes’ shoulder and waist circumference and between their waist circumference and their hips.

«We hypothesize that the figurines conveyed body-size ideals for young women,» Professor Johnson says. — «We found that the figures’ body volumes increased as they got closer to the glaciers, and obesity was not as pronounced in warmer climates.

Apparently obesity was a desirable condition, and the figures represented an idealized body for the conditions of living in the cold. An obese woman in times of food scarcity is more likely to bear a child than an undernourished woman, the researchers explain.

«These enigmatic figurines of overweight women, which appeared in hunter-gatherer cultures in Ice Age Europe, where obesity was not expected at all, are among the earliest works of art in the world,» says lead study author Professor Richard Johnson. — We show that the proportions of these figurines correlate with periods of extreme food stress.»

Many of the figurines are well-preserved and appear to have been heirlooms passed down from mother to daughter from generation to generation. Women entering puberty or in the early stages of pregnancy may have been given them in the hope of imparting the desired body weight to ensure a successful delivery.

- Increased fat mass would provide a source of energy during pregnancy and lactation, as well as much-needed thermal insulation, the authors of the paper explain.

So the spread of obesity would ensure another generation lives in a dangerous climate, scientists conclude.